Cassian the Sabaite

eclipsed by 'John Cassian of Marseilles'

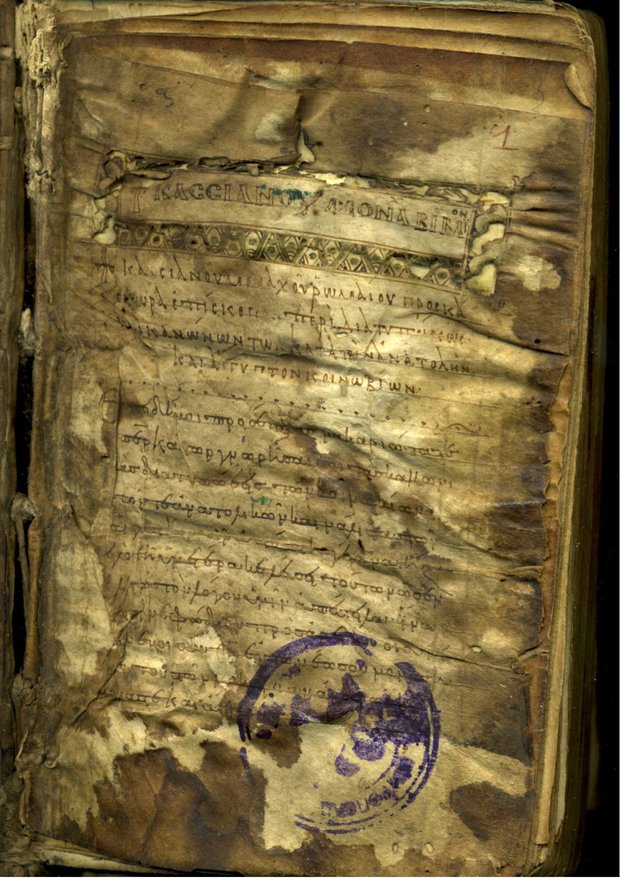

Cassian the Sabaite was an intellectual of Antiochene extraction, who was born in Scythopolis in c. 470/5. He spent six years (c. 533-539) living at the monastery of the Akoimetoi, in Constantinople. In 539 he was appointed abbot of the monastery of Souka, where he remained until October 547, when he was appointed abbot of the renowned Laura of Sabas to remain in the post only for nearly ten months until his death on the 20th of July 548. As a presbyter of the Laura of Sabas, he took part in the local synod of 536 in Constantinople and signed its acts along with Leontius of Byzantium. Codex 573, which was discovered in the Meteora monastery of Metamorphosis (the Great Meteoron), is in fact a manuscript produced in Palestine, indeed at the scriptorium of the Laura of Sabas, where Cassian was the abbot.

Cassian the Sabaite was an intellectual of Antiochene extraction, who was born in Scythopolis in c. 470/5. He spent six years (c. 533-539) living at the monastery of the Akoimetoi, in Constantinople. In 539 he was appointed abbot of the monastery of Souka, where he remained until October 547, when he was appointed abbot of the renowned Laura of Sabas to remain in the post only for nearly ten months until his death on the 20th of July 548. As a presbyter of the Laura of Sabas, he took part in the local synod of 536 in Constantinople and signed its acts along with Leontius of Byzantium. Codex 573, which was discovered in the Meteora monastery of Metamorphosis (the Great Meteoron), is in fact a manuscript produced in Palestine, indeed at the scriptorium of the Laura of Sabas, where Cassian was the abbot.

The ‘Book of Cassian’ (Codex 573 itself) was a personal companion to this erudite man being influenced by sixth-century ‘Origenism’ and definitely by Gregory of Nyssa. A spiritual son of St. Sabas, tutored by the saint himself, he became the abbot of the Laura of Sabas at the recommendation of Patriarch Peter I of Jerusalem (524-552). When this prelate suggested to the leading monks of the Great Laura that Cassian should be appointed, he presumably took into account the unstable circumstances of that period. Given the power of the Origenists at the time, Cassian’s respected personality (and moderate Origenism) was a compromise accepted by both parties. This happened in October 547 (when the Origenistic controversy was raging at the Laura itself, as well as at the New Laura and the adjacent monasteries), only four years before the Fifth Ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 553, and five years after Justinian had issued his Edictum contra Origenem (Letter to Patriarch Mennas). This edict was compiled in the Laura of Sabas itself by abbot Gelasius and other elders (which is definitely shown through ancient testimony) and was subsequently sent to Patriarch Peter I of Jerusalem (524-552), who dispatched it to Justinian it turn. The emperor immediately employed the text; he made this an imperial edict verbatim, and finally implemented it through condemnation of Origen by a local synod summoned by the patriarch Mennas at the emperor’s behest.

Cyril of Scythopolis wrote a detailed account of the death of Sabas at the age of ninety-four, in 533 AD. In this story, Cassian is described as a ‘gifted’ person, in both ethical and intellectual terms (kekosmhmevnos tõ logõ). It is remarkable that, beside Cassian the Sabaite, this chronicler attributed this characterization only to St. Sabas himself and Theodosius the Coenobiarch.

According to Cyril, Sabas was a real saint, yet it is important that his story involves Cassian’s sanctity, too. Cassian died sixteen years after Sabas. He was the abbot, and a decision was made that the body of the deceased ‘blessed Cassian’ (tou makariou Kassianou) should be interred along with that of Sabas. When the crypt was opened for the occasion, they found the body of Sabas incorrupt and with no signs of decay, and Cyril assures us that he saw this himself.

This testimony is important for an additional reason. It appears that Cassian was considered to be as exceptional a personality as to deserve to be placed next to the body of the deceased venerated founder of the Laura. It could be argued that he was placed in the crypt, which was reserved for the abbots of the monastery. During the period of fifteen years since the death of Sabas, there had been other abbots, whom Cassian succeeded, and he himself remained in the post for only ten months. The successor of Sabas was a certain abba Melitas, born in Beirut, and was chosen by Sabas himself, who had a premonition about his own death a few days before this actually occurred. The new abbot remained in office for five years until he died in September 535. He was succeeded by Gelasius (September 537- October 546), who immediately took anti-Origenist action. Then a certain Origenist monk, called George took up and remained in office for seven months (547), to be deposed by the Origenist party itself on the grounds of corruption. Therefore, if a specific site for interring the bodies of abbots had been determined, this should have happened with the body of at least one of Cassian’ predecessors, notably Melitas and Gelasius. Therefore, the findings about the incorrupt body of Sabas could have become known at least a year earlier. Still, it seems that special treatment was reserved for Cassian, because of his personality, not simply of his office as abbot.

The texts that are included in Codex 573 are imbued by a prodigious Greek Classical lore, at a time when Hellenism was a cause of defamation rather than adulation. The lesson Cassian had learnt as an Antiochene was that Aristotle rather than Plato was more appropriate in order to produce a sophisticated account of the doctrine. Following great masters such as Diodore of Tarsus, Theodore of Mopsuestia, and Theodoret, he viewed Alexandrian Platonism as a main cause of theological aberration. At the same time, however, it was clear that there was an enormous treasure enshrined in the works of Alexandrian doctors such as Origen, Didymus, and Cyril of Alexandria, which no one could afford not to avail oneself of. After a century since the passionate debate between Theodoret and Cyril of Alexandria, he felt that there were no substantial differences between the two masters, especially with respect to Christology. An Antiochene though he was, Cassian saw the feat of the Church of Alexandria. Redundant as his admonition may appear to the modem reader or to a well-groomed audience, the gist of this should not elude us: Cassian carries on the shift marked by the Evagrian return to the Origenist legacy, namely, return to intellectualism, and he seeks to build on the ancestral wisdom by crowning faith with knowledge.

The texts of Cassian are a genuine part of an uninterrupted chain of Greek writings, with technical locution and striking parallels of earlier Greek authors, both in terms of language and ideas that are entertained. There is no way for his texts to be a translation, either from Latin or from any other language. Cassian says that the pedagogy flowing from his tracts is not an invention of his own, but opinions by fathers of old. By this, he meant not only previous hermits and monks (which is the normal meaning of ‘fathers’ in Cassian and in monastic literature in general), but also influence by more sophisticated intellectuals. Normally, nevertheless, Cassian does not mention earlier writers by name, save Basil of Caesarea at a couple of points. However, it can definitely be shown that he is bowled head over heels by the technical philosophical collocation and theology of previous authors. Perusal of these texts reveals who the ‘fathers’ that supplied Cassian with his terminology were.

The author is an immensely erudite Greek, especially familiar with Plato and with the Aristotelian and Stoic ethics. His hero and flare is Gregory of Nyssa, his writings reveal an Easterner, indeed an Antiochene, and his ideas are drawn from Origen, Didymus, Evagrius, Eusebius, Clement of Alexandria, and Theodoret. Quite definitely, Cassian is an outstanding case of an Antiochene freely drawing on Alexandrian theologians, on Origenists, on eminent Greeks of Classical and Late Antiquity, without any sense of alienation from his patrimonial theological nourishment, which must have been Diodore of Tarsus, Theodore of Mopsuestia, Theodoret of Cyrrhus, and Nestorius. Had the ostensible ‘John Cassian of Marseilles’ been able to study the vast bulk of all the prolific authors who are outstandingly present behind the expressions we come upon, he would have been able to write in Greek, not in Latin. But no one did ever go as far as to claim that the figment ‘John Cassian of Marseilles’ could have either read Greek, far less to write in this language.

Cassian the Sabaite’s phraseology is not the achromatic language of a text, which is normally the case with any translation with respect to the original. Not only notions, but also a specific vocabulary (often exclusive to one or two previous intellectuals) is confidently reproduced. The author knows Hebrew and quotes from that text, mostly by memory, and sometimes Old Testament quotations are a Greek translation of his own from the Hebrew. Were it for Cassian’s texts to have been a translation from Latin, the translator would have had all the time and means to render these portions in the more or less standard Greek scriptural text. However, what we see (especially in the conferences with Moses and Serenus) is a Greek author who quotes scripture by memory and feels free to make use of paraphrased scriptural portions.

Once Cassian’s texts are scrutinised, one finds an entire library, both Christian and Greek, condensed in his succinct statements. In this library, the leading role is played not only by Gregory of Nyssa, Eusebius, Theodoret of Cyrrhus and Cyril of Alexandria, but also by Lucian of Samosata, Origen, Didymus, Evagrius, Alexander of Aphrodisias, Plutarch, Galen, Proclus, Simplicius, Damascius, John Philoponus. In other words, the writer clearly intended a return to intellectualism. In terms of philosophy, this means revisiting the Greek patrimony and making pretty much of this during a period when the Greek lore was excorcised as a daemon. In terms of theology, this meant veiled revival of Origen amidst the dark age of Justinian.

Cassian was above all an intellectual monk; and yet his moral teaching is all but imposition of a stringent life on monks. He shapes his argument and mounts his replies taking into account the variety of human physical construction, character, and needs, thus aspiring to being a corrector of the novice rather than a dogmatician. He wrote with animus, yet his animadversion is levelled against sin rather than sinners; his instruction aimed at countering cogitation of evil rather than the subsequent evil action by all those who abjure worldly and sensual pursuits in order to live in unimpaired equanimity. Keeping pace with the gist of Origenism (though hardly consciously so), Cassian inculcates righteousness with pious understanding and teaches that mastery of the body conduces to the apprehension of wisdom. For all this, he was as broadminded a man as to refuse to impose universal rules of fast, on account of the different physical construction of each human being. Each person needs a different amount and quality of food, which is a good reason for banning any universal regulation of fast. Despite its intellectualistic tenor, his text does not make as much of the dichotomy between matter and spirit as one might have expected. It was then natural for this set of texts to become a companion of monks, particularly neophytes, and, at the same time, it served as the basis for composing constitutions of new monasteries. For not only was daemonology an everyday concern to monks: anchorites are also satisfied that the dregs of evil still linger in the soul, even in one that has been reformed. It is impressive, however, that Cassian hardly ever perturbs his readers with stories of punishment after death, or at least he does so to the minimum possible, when he refers to the eight dispositions to evil.

What makes Cassian’s scholarship interesting is that he felt free to glean from all streams of Christian tradition, and he did so along with drawing on the Greek patrimony and the Oriental lore. This means that, despite specific streams of thought traced here and there in his writings, he actually saw one tradition available to him, which was the treasure of Christian and Greek patrimony.

Cassian’s work is a novel fusion. I have argued through evidence that this could have happened only during the first half of the sixth century. For we are faced with a new sort of style defiantly drawing on Greek lore, with no inflated despise against the very source of its own spiritual inspiration. Not only was Cassian familiar with Proclus’ theology, but he was also immersed in the Neoplatonic currents of his own day. His aim, however, was not to row against the persecuted resplendence of Damascius and Simplicius. Rather, he sought to equip himself with the oars of that sparkling Neoplatonic wisdom in order to formulate fresh Christian formulations, which were called for by the sixth-century challenges. Those challenges were not seen as mere doctrinal ones. The decline of the monastic ethos was only a mirror of the decline of the civic ethos, which ought to be a source of inspiration, and yet it was not. If Cassian’s writings emit an aroma of munificence, this is so because the author takes this virtue into counsel against covetousness, vainglory, greed, and pride -in short, against passions that flourished in monasteries only because they burgeoned within society in the first place. Put differently, the veracity of Cassian’s purpose cannot be assessed apart from the alimentary social setting and chain of events, which at his time both nourished and were nourished by the decline of the monastic ethos. His purpose, therefore, is to contribute to adjudication of the ravages of his time by supplying not only a nursery of prototypal monastic paradigm and rigour, but also an operative exemplar for a way out of this exigency by means of both righteous ethos and enlightenment.

In this context, disproportionate bookish consideration of Cassian the Sabaite could be pointless. For the supposed-to-be ‘Origenism’ of the sixth century had almost nothing to do with Origen’s real ideas and theories and, at the same time, authors used to condemn Origen by name in compliance with the commands of a despot such as Justinian while in essence drawing on Origen’s ideas –mostly not consciously since Origen’s ideas had been handed down through the writings of revered stars of Christian and imperial orthodoxy.

With Cassian’s texts we come upon an poised circumvention of the official state renouncing Classical Greek lore. At points, this patrimony is availed of to the extreme, thus marking an audacious revival of the spirit of acquiescence to those sages of the ‘heretics’, who had been condemned in the person of Origen. Despite the hostility that was aired in the official environment of his epoch, Cassian the Sabaite’s work turns out to be a milestone marking a decisive shift from the professed anti-Hellenism of Justinian’s era towards a spirit openly embracing the Greek patrimony –a procedure that culminated with Photius and, later still, with Michael Psellus. This process resulted in the empire’s physiognomy being transformed into a Greek one. It is irony of history that this course, though clandestine and risky, was initiated during Justinian’s reign. The monastery of the Akoimetoi was the isolated milieu where the eggs of this bold and libertarian attitude were hatched. Justinian himself was aware of this fatal development. Even though he issued his Novellae in Greek, he refers to Latin as the ‘language of our fathers’ in a sentiment of nostalgia, indeed with a taciturn mourning for the Roman character of the empire doomed to be lost and overwhelmed by a Greek identity. The emperor was of course the source of all power, which actually he put to use: the Akoimetoi were written off and, after 534, their monastery entered a process of decline, which resulted in ruin. However, Cassian’s texts reveal that much of their treasure was rescued by the amiable environment of the monastery of Studios, with Theodore Studites being the intellectual who saw the value of their heritage and the importance of Cassian the Sabaite himself.

During an early stage of his life, Cassian’s Conferences and Institutions had been written for the sake of Leontius Byzantius and his predecessor bishop Castor, the leader of an unidentified monastery, which might well have been the New Laura itself. He was at the time under the influence of Leontius and he reproduced a certain ‘Origenism’, of which Origen was not always the source. Rather, this was the product of sixth-century hearsay attributed to Origen, since monks were familiar with texts of Evagrius and Didymus rather than those of Origen. Leontius was younger than Cassian by roughly fifteen to twenty years, but Cassian outlived him by six to eight years.

Whether one reads Cassian or ‘Pseudo-Caesarius’, the text is imbued by the vocabulary of Gregory of Nyssa and the theology of Theodoret. The text of Codex Metamorphosis 573 is full of notions and technical terms which are redolent of Gregory par excellence. There are also other theologians implicitly yet distinctly present, such as Eusebius, Didymus, Epiphanius of Salamis, Theodoret, John Chrysostom, and Cyril of Alexandria. Ironically, this is the reason why it was made possible for Cassian’s writings to suffer pseudepigraphous attribution: a group of works of his are currently presented under names of others and remain under the designation ‘spuria’. I have no doubt (and my analyses in my three pertinent books about Cassian demonstrate this time and again) that such works as (Pseudo-Basil of Caesarea) Enarratio in Prophetam Isaiam, or many of Basil of Caesarea’s Sermones de Moribus, or Quaestiones et Responsiones ad Orthodoxos (currently attributed to Theodoret and alternatively to Pseudo-Justin), Synopsis Scripturae Sacrae (Pseudo-Athanasius), De Vita et Miraculis Sanctae Theclae (Pseudo-Basil of Seleucia), Oratio Quatra Contra Arianos (Pseudo-Athanasius), and texts currently attributed to ‘Pseudo-Macarius’. I am confident that future philological exploration will reveal Cassian as the author of a prodigious literary output. Moreover, Migne published two works: De Incarnatione Domini and De Sancta Trinitate under Cyril of Alexandria’s name. They are now believed to be Theodoret’s, all the more so since there is a testimony by Gennadius of Marseilles, according to which Theodoret had written a book on the Incarnation of the Lord. However, both are conspicuously present in our explorations of Cassian’s work and their possible relevance to his pen should remain a moot question calling for investigation. Furthermore, I have argued that the philological genre of treatises in the form of ‘Questions and Answers’ is a product of the late fifth- and sixth century, and Cassian was a protagonist for this sort of literature to appear.

A prolific writer though Cassian was, his name had to be associated only with monastic writings attributed retrospectively to another ‘Cassian’. Concerning the real Cassian, all that was needed was silence -neither tendentious invective, nor dispute, not even dabbling in the rest of his writings: it could suffice to attribute these writings to Athanasius, Chrysostom, and others. The true Cassian was an antecedent to be done away with. The role of ancestor was reserved for another Cassian made out of thin air. Not much was needed anyway: it sufficed to present this other ‘Cassian’ (now designated ‘John Cassian’) as having composed these writings as answers to the same problems and having deduced his stance from identical premisses. Revisiting the collection of biographies by Gennadius of Marseilles, interpolating an alleged biography of a figment called ‘John Cassian’, plus tampering with some other points of the same collection, was enough to put the real Cassian to a ‘second death’ and give rise to a ‘link between the eastern and western monasticism’ under the name of a phantom called ‘John Cassian’.

Cassian himself was treated as a heretic and his writings fell prey to mongers and forgers. The name ‘Cassian’ was purloined from a real author who was pushed to extinction. Subsequently, the existence of a phantom, which was subsequently made a skeletal phenomenon until flesh tints were applied to that, was only a matter of fissiparous reproduction. All begun with the phantasmal flesh and blood interpolated in the text of Gennadius of Marseilles, which was subsequently peppered accordingly from start to finish.

Cassian did not deserve such a fate, no matter what his occasional doctrinal aberration may have been. All the more so, since he never tried to disguise or attenuate his dues to his eminent predecessors, who are in fact those who allow us to identify him as a Greek Christian author. However, he was the perfect match: he had composed monastic tracts that were handy for the dawning western monasticism; he was disfavoured, yet not so famous as to be anathematised by name, by any synod. The bulk of his Greek manuscripts perished through destruction or neglect, or indeed through attribution to past stars of Christian literature, whereas his boldest speculations are the ones that his enemies would have been most zealous to suppress and his admirers least solicitous to shelter.

In any case, once specific expressions and forms are studied on the grounds of philology, philosophy and theology, it turns out that Cassian’s texts evince a striking semblance to works currently under such names as Clement of Rome (pseudo-Clementine), Athanasius, Chrysostom, Basil of Caesarea, Basil of Seleucia, Didymus, and various anonymous works aimed against the Jews. An entire corpus of spurious works is still waiting for exploration and for their real author to be identified. It is my firm conviction that Cassian will turn out to be the author of a large number of them.

Special mention should be made of the set of epistles under the header Amphilochia, which is currently attributed to Photius. I do not actually urge any wholesale contention against this attribution. For instance, I do not dispute the lengthy, detailed, and incisive first answer addressed to Amphilochius as being an original one by Photius. However, the similarities (some of them unique) with Cassian’s style are too many to be overlooked. The collection is so called because it was dedicated to Amphilochius of Cyzicus: he was one of the devout friends and oldest disciples of Photius, who had propounded certain questions to his master who is often mentioned therein. The edition comprises a set of questions and answers. Although, according to the prologue, these are three hundred epistles, in existing manuscripts and editions, the number is greater and more variable, and the order is not the same. Evidently, additions have been made with the passage of time, and I am not sure whether these additions could be attributed to one author alone beside Photius. What I am certain about is that a number of them were authored by Cassian. The order is different in various manuscripts and it is due to irregular additions that either some passages are treated more than once, or there is no apparent plan, or their length varies, some being mere notes, while others are almost treatises.

There is not any stunning originality in Cassian’s texts, which is also the case with Caesarius’ Erotapokriseis and the Pseudo-Didymian De Trinitate. Nevertheless, the author’s excerpts from Dionysius the Areopagite are noteworthy, and the fact that there are no less than thirty-two passages where the author repeats Theodoret almost word for word should alert Cassian’s reader to an Antiochene writer. In any event, his text brings to light use of Greek extremely rare expressions (having only a couple of precedents, and sometimes only one) which are characteristic of earlier distinguished Christian authors. Such expressions have been rendered into Latin to the letter. To posit that these Greek passages are translation from an alleged Latin original means that we are asked to believe that a Latin author who was almost ignorant of Greek language was aware of a vast number of extremely rare Greek expressions, which he originally rendered in Latin.

The specific Greek text of Cassian was extant during the second half of the sixth century and Antiochus of Palestine quoted extensively from this in the early seventh century. To posit that this Greek text is a translation also could mean that, once Cassian wrote about the rules of monasteries in Palestine and Egypt, Palestinian monks cared to translate his works from Latin so that they might learn the rules of their own monasteries from a Latin author.

The most striking case is indeed Antiochus of Palestine, who was born in the vicinity of Ancyra. This is why sometimes he is styled Antiochus of Ancyra and known as the monk (and perhaps abbot) of the Laura of Sabas. The Persians destroyed his hometown Ancyra in 619, which compelled the monks of the neighbouring monastery of Attaline to flee their home and move from place to place. Since they were unable to carry many books with them, abbot Eustathius (who had introduced Antiochus to monastic life) asked him to compile an synopsis of the Holy Scripture for their use. Antiochus obliged by writing a work known as Pandectes of Holy Scripture. He mentions only a few earlier writers by name: Gregory Thaumaturgus, Irenaeus, and Ignatius of Antioch. What he did not say, however, is that he himself drew heavily on Cassian, who had also been a monk and abbot in the same Laura of Sabas only seventy years before Antiochus himself. Vast sections of this compilation are simply word-for-word quotations from the work of Cassian the Sabaite.

Consequently, here is a strange phenomenon. Seventy years after Cassian’s death, Antiochus of Palestine setting out to produce a résumé of the teaching of Scripture, quotes from Cassian extensively and yet he does not mention his name at all. John of Damascus and Anastasius of Sinai quoted from this work, too, yet also neither of them mentions Cassian. This means that Sabaite writers, such as Antiochus and Damascenus, blacked Cassian out. If Anastasius is also considered carefully, this allows for the impression that this was an attitude of suspicion against Cassian by those who lived in the wider region of Palestine. In other words, we come upon an echo of the Origenistic controversies of the sixth century, with the file against Cassian’s name still being kept open. However, this reflects the local spirit of Palestine and the memories of the vicissitudes that had tormented the region, indeed the Laura of Sabas itself. For, by contrast, theologians of more remote theatres, such as Constantinople, treated both Cassian’s name and work with respect.

As already noted, Antiochus of Palestine wrote his Pandectes of Holy Scripture at the request of his former superior, abbot Eustathius of the monastery of Attaline, near Ancyra. The question which consequently arises is this: while living at the Great Laura and its renowned library, which contained works by all Cappadocian, Alexandrine, Antiochene and Palestinian stars of Christian theology, why should Antiochus have been in need of a translation of a work by a hardly known Latin author in order to compose his abridgement of the moral teaching of Scripture? Is it not more reasonable to infer that he deemed it handy to quote from the work of his predecessor, a Sabaite monk and abbot, namely Cassian, who had died only seventy years ago, his work was certainly on the shelves of that library, and his body was resting in the same premisses, side by side with that of St. Sabas himself?

Following publication of the three relevant volumes of my work on Cassian the Sabaite, there have been scholars, especially ones with specific religious allegiances, who are all but prepared to disown the established myth concerning ‘John Cassian’ and they mourn ‘eighty years of scholarship’ on a fictitious Latin writer who turned out to be a mere figment. They are anxious to reject the dreadful thesis that the existing Latin text ascribed to ‘John Cassian of Marseilles’ is the product of a massive interpolation and forgery based on supressed (and far less extensive) work by Cassian the Sabaite. But once the techniques of the fifth-to-sixth century era are considered, one has to allow the following as a consequence: in order to say a few things concerning the rules of monasteries and other relevant topics, that fabled ‘John Cassian of Marseilles’ had at his disposal the abundance of means required for the production of a Latin original such as the one preserved today, which is far more extensive than the authentic Greek work that Cassian the Sabaite actually composed.

When a codified Rule of Cassian by an unknown author appeared is not quite certain, but definitely it was circulating shortly after Cassian the Sabaite’s death, on 20th July of the year 548 AD. This was before the appearance of the Benedictine Rule that made use of Cassian, whose writings were ‘incorporated into the Benedictine Rule’. The Rule of the Master (Regula Magistri) was a text drafted and circulated in the sixth century: its earliest Latin manuscript, in Paris, goes back to about 600. Owen Chadwick knowledgeably notes: “I have shown reason to think that the text of Cassian suffered touching in its early centuries … the text of Cassian suffered alteration at the hands of a copyist who knew the Master.”

This is the heart of the matter, yet the sagacious scholar did well as far as he went, but he did not go far enough. The Rule of the Master by the anonymous translator is the bridge between Cassian the Sabaite and the interference that attributed his works retrospectively to an allegedly existent mediocre fifth-century presbyter John Cassian. If ‘use of Cassian’ by the Regula Magistri is ‘more faithful than the use of Cassian by Benedict’, this is so because the anonymous Latin rendering of the Rule of the Master actually meant to render Cassian the Sabaite. This translation was the gate for the West to discover the monk of the St. Sabas Monastery and retrospectively for a series of copyists to make one ‘Cassian’ out of two, if indeed any ‘John Cassian’ did ever exist at all, which I dispute.

It has been believed that, all of a sudden, John of Damascus (c. 676-749) appeared on stage in order to offer an account of the doctrine, which may not have been original, yet it rendered the spirit of previous theologians. Cassian fills the gap. For he is the synthesis of Gregory of Nyssa, Theodoret, Theodore of Mopsuestia, Cyril of Alexandria, Didymus, Evagrius. Cassian is not the meeting-point between East and West: quite simply, St. Benedict and his successors drew heavily on his work. Rather, he is a continuation, as well as fresh start of the uninterrupted eastern tradition well into the sixth century. This process was accomplished by Sabaite intellectuals and nourished in the libraries, as well as in the ascesis, of the monastery of the Akoimetoi. Antiochus and Damascenus, who both drew on the Sabaite library that was available to them within the same premises, took up Cassian. Scribe Theodosius, who reproduced ‘the book of Cassian’ (Meteora, Codex Metamorphosis 573) was a Sabaite monk, as Codex 76 and Codex 8 of St. Sabas demonstrate.

In the year 1616, the works ascribed to ‘John Cassian’ were published and commented on by Alard Gazeus or Gazet, a Benedictine monk of St. Vaast’s at Arras, first at Douay (and afterwards with more ample notes at Arras, in 1618). By that time, the writings of the true abba Cassian suffered interpolation and tampering, and it could make little sense to explore the forgeries entirely. If the alleged ‘John Cassian’ wrote anything at all, he wrote in Latin (such as his work on Nestorius) although he is believed to have had an extremely poor knowledge of Greek. How this opinion about knowledge of Greek could be sustained, I do not see. This may well be one more myth surrounding this obscure Scythian figure, which seems to have been made up out of thin air, and the hubristic falsehood goes as far as to asseverate that a minor allegedly existent less than a minor author was supplied with means to write and publish (by copyists) a set of writings as expansive as those of the greatest stars of Christian literature, as, for example, John Chrysostom.

Cassian the Sabaite himself tells us implicitly, yet clearly, that at the time when he was writing his treatises for the sake of bishop Castor, he lived in a monastery pretty near the Cave of Nativity. The place which he intimates should be the Laura of St. Sabas itself, which is located near Bethlehem. We know that Cassian spent time in the Laura of Sabas, where he became a presbyter and, at the time when he was appointed abbot of the Sabas monastery, he was the abbot at Souka. It is therefore probable that he wrote to Castor while he was still a monk at the Great Laura of Sabas, since when he wrote to Leontius (evidently before 536) he notes that his treatises addressed to Castor had been written ‘a long time ago’. His works addressed to Leontius were written while he was living at the Laura of Sabas, which is indeed near Bethlehem, and they should be dated between the years 514-519, namely the period during which Leontius had been banished from the Laura of Sabas. The work addressed to Castor dates earlier still.

All the evidence setting out to ascribe all writings to the figment ‘John Cassian of Marseilles’ dates well after the death of Cassian the Sabaite. This fact cannot be dispensed with. The original manuscripts of works of a ‘presbyter’ who died in honour are not older than the seventh century and acclamation for his alleged achievements are all lost, which is extremely strange. Even the alleged anonymous condemnation of John Cassian, of which Owen Chadwick tells us in an articulate recounting, dates no earlier than in a manuscript of the eighth century. Furthermore, all biographies which represent clerics of the fifth century as having been fascinated by the Institutes and Conferences of John Cassian (Fulgentius of Ruspe, Caesarius of Arles) are desperately retrospective and far too later ones to count as historical evidence.

Consequently, anyone who professes the current claim that a certain Latin author called ‘John Cassian’ wrote in Latin has also to concede the following.

1. The Greek text, taken as a translated one, has been automatically and heavily loaded with distinct and all too rare technical expressions drawing on a long tradition in the Greek Christian East, which are however absent in Latin literature. These expressions have a traceable history, as they were handed down from one Greek theologian to another during the first six centuries, but they have no history in Latin whatsoever.

2. A Latin author such as ‘John Cassian’, allegedly addressing a Latin audience, felt it necessary every now and then to interlace his text with Greek terms and expressions, even Greek scriptural portions.

3. Some striking Neoplatonic expressions and notions applied by Cassian in theology are the fortuitous result of a Greek translation from Latin.

My thesis is, therefore, plain: the claim that this text has been originally written in Latin turns out to be too extravagant and too unreasonable to allow.

There is a characteristic aversion to rendering Cassian’s name in English literature in the way it should be rendered. Whereas the name is Kassianos and the fictitious ‘John Cassian’ is named ‘Cassian’, Cassian the Sabaite himself seems to cause embarrassment. In the sparse cases where mention has to be made of Cyril of Scythopolis referring to this Sabaite monk and abbot, a special translation is reserved for the name Kassianos: this is rendered ‘Cassianus’ or ‘Kassianos’, never Cassian. Likewise, a scholar who set out to write a life of Theodore Studites and came upon mentioning Cassian, resolved that ‘John Cassian’ might have exerted some influence upon Studites, even though Studites refers to Cassian, not to any ‘John Cassian’. The modern author defiantly goes on that ‘Greek resumés of Cassian may have been available to Theodore’ Studites, as if the abbot of Stoudios needed a minor Latin author to be retailed in Greek, so that he could learn how monastic life was conducted in the Greek-speaking East. Although Theodore Studites mentions ‘Cassian’ (not ‘John Cassian’), the modern author in his Index decided to classify this author as ‘John Cassian’.

Quite evidently, to scholars, Kassianos is an inconvenient stumbling block and a flustering synonymy. But although it has appeared that the Sabaite monk and abbot Kassianos mentioned by Cyril of Scythopolis can conveniently be left a skeletal figure, my contention is that both his texts and sufficient historical testimony can flesh him out.

The Dominican scholar A. J. Festugière remarked that only some erudition suffices for any one who deals with ideas to reach any conclusion one likes (en ce qui touche les idées ... on peut, avec quelque erudition, soutenir ce qu’on veut). This holds all the more true once a specific conclusion was desirable not by only ‘one’ but many quarters having set out to contrive a Latin figure supposed to have been ‘the father of western monasticism’ and to represent a figment called ‘John Cassian’ as a historic figure. Latin translators have normally lengthened, as well as abridged, amended or omitted certain passages, which has resulted in a text suitable to a scholastic paraphrase of Cassian’s texts being attributed to a mirage called ‘John Cassian of Marseilles’. The fable that ‘John Cassian’ was indeed the author of these renderings was thereby reinforced, at least in the minds of those to whom the original texts of Cassian the Sabaite were not available. Besides, Greek translations of ‘John Cassian’s’ works were produced and proliferated later, which contributed to the impression that Latin, not Greek, was their original language. Attentive scholars such as Franz Diekamp and Otto Chadwick were not unwary, yet they could not suspect that a Greek text such as that of Codex Metamorphosis 573 was there to render the ‘Latin-factor’ a mendacious invention.

Codex Metamorphosis 573 was written at the scriptorium of the Laura of Sabas in Palestine, and it contains an original Greek text, from which a series of subsequent authors quoted, especially Sabaite and Studite intellectuals. Besides, Cassian is the author not only of the works currently ascribed to the mirage called ‘John Cassian’, but also of a long series of spurious or anonymous texts, which currently appear under the names of Christian celebrities. One of them is the Scholia in Apocalypsin, which not only did he author but also cherished in his own companion book, the ‘Book of Cassian’ (Codex Metamorphosis 573 itself) is the most ancient reproduction of which we know. In determining the author of the Scholia in Apocalypsin, Cassian had in the first place to be resurrected as a writer.

Cassian is a commanding figure that demands our attention and deserves a hearing. This is the task I have essayed to fulfil in three volumes, namely, A Newly Discovered Greek Father (2012), The Real Cassian Revisited (2012), and An Ancient Commentary on the Book of Revelation - A Critical Edition of the Scholia in Apocalypsin (2013).